新入荷

再入荷

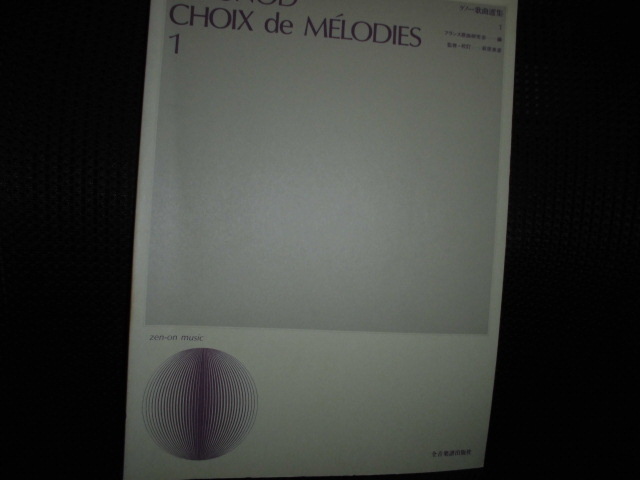

洋書 輸入楽譜ドニゼッティ ソプラノ・アリア集 リコルディ社 ピアノ伴奏付 ヴォーカルスコア集アンナ・ボエーナマリア・ストゥアルダほか

タイムセール

タイムセール

終了まで

00

00

00

999円以上お買上げで送料無料(※)

999円以上お買上げで代引き手数料無料

999円以上お買上げで代引き手数料無料

通販と店舗では販売価格や税表示が異なる場合がございます。また店頭ではすでに品切れの場合もございます。予めご了承ください。

商品詳細情報

| 管理番号 |

新品 :59915140978

中古 :59915140978-1 |

メーカー | 7af21259adab | 発売日 | 2025-04-24 19:22 | 定価 | 4980円 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| カテゴリ | |||||||||

洋書 輸入楽譜ドニゼッティ ソプラノ・アリア集 リコルディ社 ピアノ伴奏付 ヴォーカルスコア集アンナ・ボエーナマリア・ストゥアルダほか

ご覧下さりありがとうございます。画像の後に、商品説明がございます。

本の出品です。

【即決】ご入札いただければすぐにお取引が成立します。

洋書 楽譜 輸入楽譜 ドニゼッティ ソプラノのためのアリア曲集 リゴルディ社

ソプラノ・ピアノ伴奏 声楽 歌曲 イタリア語 解説付き

Donizetti Per Soprano

Arie del Melodramma Italiano

作曲者:DONIZETTI, Gaetano ガエターノ・ドニゼッティ

商品名:Arie per Soprano ソプラノのためのアリア

楽器・形態:オペラ ヴォーカル・スコア/アリア・ピース

出版社:Ricordi

1994年

約30.1x23x0.7cm

70ページ

※翻訳は参考程度にお読み下さい

リコルディ社発行、ソプラノのための、オペラのヴォーカルスコア曲集。

リコルディ社は、特に声楽の分野で世界的に人気の出版社。

本文はイタリア語です。

各曲のあらすじ解説は、イタリア語・英語・ドイツ語・フランス語。

■収録曲

「アンナ・ボレーナ」より Piangete voi ?

「アンナ・ボレーナ」より Al dolce guidami castel natio

「ファウスタ」より Tu che voli, gia spirto beato

「エステ家のパリジーナ」より Sogno talor di correre

「ルクレツィア・ボルジア」より Com'e bello ! Quale incanto

「マリア・ストゥアルダ」より Oh nube ! che lieve

「マリア・ストゥアルダ」より Nella pace del mesto riposo

「ロベルト・デヴェリュー」より E Sara in questi orribili momenti pote lasciarmi ?

「ロベルト・デヴェリュー」より Vivi,ingrato,a lei d'accanto

「ポリウト(殉教者)」より Di quai soavi lagrime

「ロアン家のマリア」より Havvi un Dio che in sua clemenza

「カテリーナ・コルナーロ」より Vieni o tu, che ognor io chiamo

アンナ・ボレーナ 第2幕 第2場と最後のアリア

「Piangete voi?「 」Al dolce guidami castel natio「 」Al dolce guidami castel natio」

ファウスタ、第3幕、祈り 「Tu che voli, gia spirto beato」(飛ぶ者よ、すでに祝福された魂よ)

歌劇「パリジーナ」第2幕 ロマンツァ 「Sogno talor di correre」(私は時々走る夢を見る)

ルクレツィア・ボルジア、プロローグ、ロマンツァ "Com'e bello!なんという魅惑

マリア・ストゥアルダ 第1幕 アリアとカバレッタ

マリア・スチュアルダ、第1幕、アリアとカヴァレッタ 「ああ、ヌーヴェ!」「チェ・リーヴェ」「メスト・リポーゾの平和の中で

ロバート・デヴリュー 第3幕 情景とエリザベートのアリア "そしてサラはこの恐ろしい瞬間に私を捨てられるだろうか?」

「恩知らず、彼女のそばで生きて」

ポルート、第1幕、パオリーナのカヴァティーナ "Di quai soavi lagrime」

マリア・ディ・ローハン、第3幕、祈り 「Havvi un Dio che in sua clemenza」(慈悲深い神がおられる)

カテリーナ・コルナーロ プロローグ、ロマンツァ 「Vieni o tu, che ognor io chiamo」(さあ、私が毎日呼ぶあなたよ)

はじめに

ガエターノ・ドニゼッティのシリアスなオペラからソプラノ・アリアを集めたこの曲集は、ほとんどすべての場合において悲劇的な運命をたどる女性たちを描いた肖像画と言える。アンナ・ボレーナ』(1830年)から『カテリーナ・コルナーロ』(1844年)までの14年間に作曲者が書いたロマンティックなドラマの中で語られる出来事を、これらの登場人物は、ほとんど常に無意識のうちに動かしている。

王族や高貴な女性たちの動機、期待、不安、心の秘密、吐露、祈りは、ほとんど全員が歴史のページから飛び出してきたが、19世紀の悲痛な生き物として自由に改造され、作曲家が彼女たちの魂の最も深く隠された部分を裸にする仕事を任せた場面、アリア、カヴァティーナ、ロマンサ、カバレッタの中で、オペラの構造を支配する不変の慣習に従って凝集された。ドニゼッティの70を超える演劇作品の中で、犠牲となる運命にあるヒロインを中心に展開されるオペラは、コンパクトであると同時に変化に富んだ核を形成している。

その頂点に立つのは、言うまでもなく、愛に狂わされたランメルモールのルチアである。ほとんど全員が死の予感で結ばれているが、これらの抜粋で表現される主人公たちは、彼らが巻き込まれる芝居の筋書きのさまざまな波乱と、歌によって明らかにされる多様な性質と感情的特質によって、互いに区別される。静的な状況を表現する曲もあれば、変化、発展、音域の移行を示す曲もある。

アンナ・ボレーナがパーシーとの若き日の恋を幻覚のように語る場面から、ファウスタが自分の中傷のせいで継子が死刑になったことを悔やむ場面へ、パリジーナが幼い頃の無邪気な喜びを回想する場面から、ルクレツィア・ボルジアの母性愛が露わになり、彼女が眠る秘密の息子に思いを馳せる場面へ; マリア・スチュアルダは、彼女の懐かしさが、幸せな若いころの政治と恋で、憎むべきライバルとの出会いが迫っていることへの不安に沈んでいるとき、エリザベッタは、お気に入りのデヴリューの裏切りに疲れ、苦悩しているが、それにもかかわらず、勝利したライバルとの長寿を願い、寛大である; 異教徒に迫害されたキリスト教新教徒の共同体の穏やかな歌声に感動するパオリーナの涙から、恋人の死を不本意な形で招いたローハン伯爵夫人が、自分の潔白を天が見届けてくれるよう求める場面、愛する人の到着を心待ちにするカテリーナ・コルナーロの愛の宣言まで。

このような多様な心情に対応して、形式的な構造(これは次第に発展していく)、全体的な音楽的発明、そして特に声楽の書き方にも多様性がある。ドニゼッティ、ベッリーニ、メルカダンテ、そして同時代に活躍した作曲家たちの時代に、イタリアの本格的なオペラで主流となったのは、ドラマティック・コロラトゥーラ・ソプラノ(ドラマティックなコロラトゥーラ・ソプラノ)であった。この新しいタイプの声は、ジュディッタ・パスタ、マリア・マリブラン、ジュゼッピーナ・ロンツィ=デ・ベグニス、カテリーナ・ウンゲルのような、当時の偉大なドラマティック・コロラトゥーラ・ソプラノたちの解釈の資質によって確立されたもので、彼らは非常に広い音域に恵まれており、力強い宣言から滑らかな叙情、そして全音域をカバーする向こう見ずな俊敏なパッセージまでを難なくこなすことができた。ドニゼッティは、新しいオペラを作曲する際、初演する歌手の特別な才能を際立たせ、それを最大限に利用することを常に実践していたからである。

ドニゼッティと同時代のソプラノ・アリアでは、華麗なパッセージとダイアトニックに伸びるフレーズの共存が、『椿姫』以降のロッシーニの声楽曲とヴェルディの声楽曲を結びつけるために歴史的に必要な妥協点だった。この2つの様式的要素の結合が時に強引に感じられること、また、伸びやかな旋律の途中にコロラトゥーラを挿入することが、慣習に左右されて不自然に聞こえることがあることは認めなければならない。しかし、ドニゼッティの音楽において、「コロラトゥーラはほとんど常に、強め合う機能を持っている」ことも事実である。登場人物がどのような感情を表現しているにせよ、トリルと華麗な装飾は、感情を強める描写のためにある時点で挿入される」(R.チェレッティ)。

この曲集に収録されている9曲は、さまざまな条件を満たすことを目的に選ばれているが、そのすべてが重要である。ひとつは、ドニゼッティがその芸術的キャリアの中で最も恵まれた15年間に作曲したシリアスなオペラにおけるソプラノのための作品を、スペースの許す範囲内で、多様かつ代表的なパノラマとして提供することである。その他の要件も念頭に置かれている: 有名なアリアと、それほど有名ではない、あるいはまったく有名ではないが、その本質的な資質が知られ、評価されるに値するアリアが交互に演奏される; ファウスタの祈り、パオリーナのカヴァティーナ、マリア・ディ・ローハンの祈りといった限られたサイズの作品と、パリジーナのロマンツァ、ルクレツィア・ボルジアのアリア、カテリーナ・コルナーロのロマンツァ、アンナ・ボレーナの情景と最後のアリア、マリア・ストゥアルダのアリアとカバレッタ、エリザベッタの情景と『デヴリュー』の最後のアリアといったスケールの大きな作品が、「肖像画のギャラリー 」として交互に展示されている; また、この曲集に収録されている曲は、要求される声楽のレベルも異なっている。

収録曲の楽典は、入手可能な資料(最初に印刷されたピアノ・リダクション、楽譜)に基づいており、2つの場合(マリア・ストゥアルダとポリュート)は、リコルディが編集した批評版に基づいている。これらのテキストは、特に声楽パートの色彩とフレージングに関して、この曲集の一部であるシリーズが実用的な目的で使用されることを念頭に、慎重に改訂されている。各番号の前に付された歴史と背景に関する注釈と、ピアノ・パートに付された管弦楽器に関する略語は、これらの抜粋を研究し演奏しようとする歌手にとって有益な、さらなる情報を提供している。

アンナ・ボレーナより

全3幕のオペラ・セリア。フェリーチェ・ローマニによるリブレットは、M.-J.シェニエの『アンリ8世』(1791年、パリ)に由来するイッポリト・ピンデモンテの悲劇『エンリコ8世とアンナ・ボレーナ』(1816年、トリノ)による。

1830年秋、ドニゼッティはミラノのカルカーノ劇場に招かれ、カーニバルの開幕を飾る新作オペラを作曲した。11月初め、作曲家はタイトルロールを歌うことになっていたジュディッタ・パスタが所有するコモ湖畔の別荘に移り住み、1ヵ月後にはオペラを完成させた。1830年12月26日に上演され、大成功を収めた。

リブレット イングランド王ヘンリー8世が、3番目の妻となるジェーン(リブレットではジョヴァンナ)・シーモアに夢中になったため、2番目の妻アンナ・ボレーナと疎遠になったという有名な情事を扱ったもの。

国王はアンナを拒絶するため、アンナが若い頃に愛したリッカルド・パーシー卿との結婚の誓いを裏切ったことを告発する。アンナは無罪を主張するが、死刑は免れない。

アンナの場面 「Piangete voi? 」と最後のアリア 「Al dolce guidami castel natio」。第2幕、第12場。

ロンドン塔に幽閉され、メイドたちに囲まれたアンナは、運命が成就するのを待っている。パーシーの憤慨を恐れ、そして自分が生まれ、幸せな青春時代を過ごした場所で、二人の愛を嬉しそうに回想する。

泣いているの?なぜ涙を流すの?今日は私の結婚式の日。王が私を待っている...祭壇は照らされ、花で飾られている。私の白いマントをすぐにお授けください。

私の髪をバラの花輪で飾って...。パーシーには内密に、王の命令だ。

[合唱 おお 悲しみの思い出よ!]

誰が悲しんでいる?

誰がパーシーのことを?私に彼を見せないで、彼の視線から隠れていましょう。無駄だ 彼が来る 私を非難し...叱責する ああ お許しください...

(私は惨めです。この惨めさから私を連れ去ってください。笑ってる?ああ、嬉しい!... 私はここで一人では死なない!

私が生まれた愛しいお城へ、緑のプラタナスの木々へ、今もせせらぎが聞こえる穏やかな小川へ、私を連れ戻してください......あそこでの私たちの愛の日々を、私たちが耐えてきたすべての悩みを忘れて......。

Indicazioni strumentali - Instrumental Designations Indications concernant l'instrumentation - Instrumentale Hinweise

Prefazione

Preface

Preface

Vorwort

Anna Bolena, atto II, Scena e Aria finale

"Piangete voi?" "Al dolce guidami castel natio"

Fausta, atto III, Preghiera "Tu che voli, gia spirto beato"

Parisina, atto II, Romanza "Sogno talor di correre"

Lucrezia Borgia, Prologo, Romanza "Com'e bello! Quale incanto"

Maria Stuarda, atto I, Aria e Cabaletta

"Oh nube! che lieve" "Nella pace del mesto riposo"

Roberto Devereux, atto III, Scena e Aria di Elisabetta "E Sara in questi orribili momenti pote lasciarmi?"

"Vivi, ingrato, a lei d'accanto"

Poliuto, atto I, Cavatina di Paolina "Di quai soavi lagrime"

Maria di Rohan, atto III, Preghiera "Havvi un Dio che in sua clemenza"

Caterina Cornaro, Prologo, Romanza "Vieni o tu, che ognor io chiamo"

PREFACE

This collection of soprano arias from serious operas by Gaetano Donizetti could be described as a of portraits depicting female characters who meet a tragic destiny in almost every case. These characters set in motion Palmost always involuntarily the events recounted in the romantic dramas written by composer in the fourteen years which separate Anna Bolena (1830) from Caterina Cornaro (1844). the

The motivations, the expectations and the anxieties, the secrets of the heart, the effusions and the prayers of royal or noble women, almost all of whom stepped out of the pages of history but who were freely remodelled as sorrowful creatures of the 19th century, coagulated in accordance with the immutable convention which rules operatic structure in the scenes, arias, cavatinas, romanzas and cabalettas to which the composer entrusted the task of laying bare the most deeply concealed part of their souls. Amongst Donizetti's theatrical works - amounting to more thaoteventy ideand the operas which revolve around heroines destined to be victims form a nucleus that is both compactravel varied at the same time.

The place of honour is occupied, needless to say, by Lucia di Lammermoor, driven mad by love. Almost all united by presentiments of death, the protagonists who express themselves in these extracts are distinguished from each other by the differing vicissitudes of the theatrical plots they are involved in, and by the diverse natures and emotional qualities revealed by their singing. The palette of sentiments is very varied; some pieces express a static situation, whereas others present changes, developments, transitions of register.

We pass from Anna Bolena's hallucinating evocation of her youthful love for Percy to Fausta's remorse that her slanders have caused her stepson to be condemned to death; from Parisina's serenity while she recalls the innocent joys of her childhood to the disclosure of Lucrezia Borgia's maternal love as she contemplates her secret son asleep; from Maria Stuarda, when her nostalgia for submerged by anxiety about her imminent meeting with her implacable rival in her happy ppy youth is politics and in love, to soliloquizing Elisabetta, tired and distressed by the betrayal of Devereux, her favourite, but magnanimous nonetheless in wishing him a long life with her victorious rival; from the tears of Paolina, moved by the serenity of the singing of a community of Christian neophytes persecuted by the pagan authorities, to the Countess of Rohan, who has been the involuntary cause of her lover's death and who calls on heaven to witness her innocence, to Caterina Cornaro's declaration of love as she anxiously awaits the arrival of her beloved.

To match this variety of sentiments there is a corresponding variety of formal structures (which become increasingly developed), of overall musical invention, and in particular of vocal writing. The type of high female voice which predominated in serious Italian opera in the era of Donizetti, Bellini, Mercadante and their lesser contemporaries was what is now designated by the term soprano drammatico di agilita (dramatic coloratura soprano), because it embraced both the belcanto tradition and the powerful attack and vehemence required by the romantic aesthetic. This new type of voice established itself due to the interpretative qualities of the great dramatic coloratura sopranos of the day such as Giuditta Pasta, Maria Malibran, Giuseppina Ronzi-De Begnis and Caterina Ungher, who were endowed with a very wide range and could pass with no difficulty from vigorous declamation to smooth lyricism and on to passages of daredevil agility covering the entire range. These were qualities which Donizetti exploited with shrewd mastery, since it was his unvarying practice when composing a new opera to highlight - and take full advantage of the particular gifts of the singers who were to perform it at the premiere.

In soprano arias by Donizetti and his contemporaries, the coexistence of florid passages with diatonically extended phrases was the compromise which was historically necessary to connect Rossini's vocal writing with that of Verdi after La traviata. It must be acknowledged that the union of the two stylistic components sometimes seems forced, and that the insertion of coloratura in the middle of an extended melody can sound unnatural, dictated by convention. But it is also true that in Donizetti's music "coloratura nearly always has an intensifying function. Whatever sentiment the character is expressing, the trill and the florid embellishment are inserted at a certain point to depict strengthening emotion" (R. Celletti).

The nine pieces in this collection have been chosen with the aim of fulfilling different requirements, all of them important. The first is to offer a panorama that is varied and - within the limits permitted by space- representative of Donizetti's writing for soprano in the serious operas he composed during the fifteen most fortunate years of his artistic career. Other requirements have also been borne in mind: famous arias alternate with others which are less famous, or are not at all famous but which deserve to be known and appreciated for their intrinsic qualities; there is also an alternation to return to the idea of a "portrait gallery" of pictures of limited dimensions (Fausta's prayer, Paolina's cavatina, Maria di Rohan's prayer) with larger-scale compositions (Parisina's romanza, Lucrezia Borgia's aria, Caterina Cornaro's romanza) and with more extended pieces (Anna Bolena's scene and final aria, Maria Stuarda's aria and cabaletta, Elisabetta's scene and final aria from Devereux); the items in the collection also demand differing levels of vocal accomplishment.

The musical texts of the extracts are based on the available sources (the first printed piano reductions; the scores); in two cases (Maria Stuarda and Poliuto) they are based on the critical editions edited by Ricordi. These texts have been carefully revised, particularly concerning the colour and phrasing of the vocal parts, in the knowledge that the series of which this collection is a part will be used for practical purposes. The notes on history and background which precede each number and the abbreviations on the piano part referring to orchestral instruments provide further information which will be useful for singers wishing to study and perform these extracts.

1

From Anna Bolena

Opera seria in 3 acts. Libretto by Felice Romani, after the tragedy Enrico VIII ossia Anna Bolena by Ippolito Pindemonte (Turin, 1816) who had derived it from Henri VIII by M.-J. Chenier (Paris, 1791).

In autumn 1830 Donizetti was invited by the Teatro Carcano in Milan to compose a new opera for the inauguration of the carnival season. At the beginning of November the composer moved to the villa on Lake Como owned by Giuditta Pasta, who had been engaged to sing the title role, and a month later he had finished the opera. It was performed on 26 December 1830, with a triumphant outcome.

The libretto. This deals with the famous amorous intrigue by Henry VIII, King of England, who is estranged from his second wife, Anna Bolena, because he is infatuated with Jane (Giovanna in the libretto) Seymour, who becomes his third wife.

In order to repudiate Anna, the King accuses her of having betrayed her marriage vows with Lord Riccardo Percy, whom she loved in her youth. Anna declares herself innocent, but does not escape the death sentence.

Anna's scene "Piangete voi?" and final aria "Al dolce guidami castel natio". Act II, scene 12.

Imprisoned in the Tower of London and surrounded by her maids, Anna is waiting for her destiny to be fulfilled. She cheers up those who are with her, but then her mind becomes confused: she raves, talks about her wedding. fears Percy's resentment, and then happily recalls their love, in the places where she was born and spent a happy youth.

Are you weeping? Why those tears?... Today is My wedding day. The King is waiting for me...the altar is Illuminated and decorated with flowers. Give me My white mantle at once; adorn my hair

With my garland of roses... Do not let Percy know; the King ordered it.

[Chorus Oh! Mournful memory!]

Oh! Who is grieving?

Who spoke of Percy?... Do not let me see him; Let me hide from his gaze. In vain. He is coming. He accuses me... he rebukes me. Ah! Forgive me...

(she weeps) I am wretched. Take me away from this Utter misery. You are smiling?... Oh joy!... I am not going to die here alone!

Lead me back to the dear castle Where I was born, To the green plane trees, To the peaceful stream That still murmurs Give me back one day Of our love there, Forgetting all the troubles We have endured.

and more

★状態★

1994年のとても古い本です。

外観は全体的に読みしわめくりじわや小きずあり、天小口経年並ヤケしみあり、

ほかは通常保管によるスレ程度、

本文経年並ヤケ、周縁部などに経年しみありますが、目立った書込み・線引無し、

問題なくお読みいただけると思います。(見落としはご容赦ください)

オークションにも滅多に出ない、貴重な一冊です。

古本・中古品にご理解のある方、この機会にぜひ宜しくお願いいたします。

★お取引について★

■商品が到着しましたら、必ず「受取連絡」のお手続きをお願い申し上げます。

■中古品です。それなりの使用感がございます。

モニタのバックライトの作用により、写真画像は実際よりきれいに見えがちです。

■絶版・廃盤、一般の書店で販売されない限定販売、

書店や出版社で在庫切れである、またはその他の理由により、

定価に関係なく相場に合わせて高額となる場合があります。

■「かんたん決済支払明細」の画面を保存・印刷することで領収書に代えさせて頂きます。

■PCよりの出品です。携帯フリマサイトのようにすぐにご返信はできかねます。

■かんたん決済支払期限が切れた場合、連絡が取れない場合、

落札者都合にてキャンセルいたします。

■土・日・祝日は、取引ナビでの応答・発送をお休みしております。

他に連絡・発送のできない日は自己紹介欄に記載しております。

■万一、商品やお取引に問題があった場合は、いきなり評価ではなく、

取引ナビにてご連絡ください。

誠実に対応いたしますので、ご安心いただけますと幸いです。

■上記の点をご了承頂ける方のみ、

ご入札くださいますようお願い申し上げます。

★商品の状態について★

Yahoo!オークションが定める基準をもとに、出品者の主観により判断しています。

以下は公式ページより選択の目安より転載します。

新品、未使用…未開封の新品、または購入から時間がたっていない一度も使用していない商品

未使用に近い…中古ではあるが数回しか使用しておらず、傷や汚れがない

目立った傷や汚れなし…中古品。よく見ないとわからないレベルの傷や汚れがある

やや傷や汚れあり…中古とわかるレベルの傷や汚れがある

傷や汚れあり…中古品。ひとめでわかるレベルの大きな傷や汚れがある

全体的に状態が悪い…中古品。大きな傷や汚れや、使用に支障が出るレベルで不具合がある。ジャンク品など。

他にも出品しています。ぜひ御覧ください。

↓↓↓出品中の商品はこちら↓↓↓Click here!